Many thanks to Qian Cai for sharing how T’ai Chi has helped her on and off the tennis court.

“Relax the body,” “bend the knees,” “turn the center,” Sensei Hiromi’s soft voice spoke to me in my head, as I tried to remind myself of a few fundamentals. No, I was not practicing T’ai Chi. I was on the tennis court, body lowered, eyes on the ball in my opponent’s tossing hand, and getting ready for the next point.

An enthusiastic tennis player, I tore my ACL a few years ago on the tennis court. The surgeon told me firmly that without an ACL replacement surgery, I would not be able to play tennis anymore. My physical therapist, on the other hand, suggested that I might be a “coper”– someone who could bypass the surgery by improving the leg muscle strength and balance to compensate for the lost function of a critical knee ligament.

I thought of trying T’ai Chi – a series of slow movements I deemed an “old person’s pastime.” As a young child growing up in China, I watched my grandpa do it every morning at the community park with many other seniors. But at that moment, T’ai Chi’s gentleness, or old-people-friendliness, beckoned to me and seemed to be exactly what I needed.

From the 14 steps, to 33, 66, and 100 steps, four long years passed. What a learning and enriching experience! Despite several internal struggles to give up at the beginning, I stuck with it and gradually noticed the mental and physical benefits, including the keen recognition that it was having an amazing, unexpected positive effect on my tennis game. I considered myself, in hindsight, truly fortunate to have stayed on long enough to experience first-hand the beauty and wisdom of T’ai Chi.

Because of T’ai Chi’s slow and highly deliberate movements and the emphasis on correct posture and stance, my quadriceps become stronger, which has helped to significantly control my knee movements and reduce knee stress. My posture is more aligned with the energy flows, known as “qi”, which, when the paths are cleared, nourish and soften the joints. My mind has become more relaxed, calm, and clear and less reactive.

In addition to these great health benefits, T’ai Chi taught me valuable tennis lessons I would never have imagined. As a direct result, not only am I able to continue to play tennis contrary to my surgeon’s prediction, I play better, rising from 3.5 to 4.0 last year in the United States Tennis Association ranking. I was thrilled to realize the similarity and connection between the two seemly opposite forms of exercise.

- With an ACL rupture I may not run as fast or pivot/cut as sharp, but I learned to be more strategic and purposeful with every shot, or “move” as in T’ai Chi. I also learned to be more relaxed, focused, and not hurried on the court.

- I learned that “bending the knees” and “sinking the body low” are good preparation and make it easier to move around on the court more quickly.

- I learned in order to generate power and speed, “center turn” is much more effective and critical than swinging an arm or shoulder.

- I applied the rule of “70-30” often. Instead of going all out and playing aggressively, I remembered to save 30 percent of the energy/effort for the situations when more is needed.

- Through T’ai Chi, I came to appreciate my tennis coach, Jim Labinski’s motto of “zen tennis”, which is also his email address. For a fast-moving sport like tennis, “zen” is, surprisingly (or not surprisingly), the key, not “faster” or “stronger.” Often before a match, I do a quick T’ai Chi warm up and when I anticipate a highly competitive match, I make myself mentally ready with a standing meditation. It is amazing how effective these techniques are.

I love tennis, and I love T’ai Chi. I couldn’t be more grateful that through a knee injury, I discovered and developed a new passion, which in turn, quietly helped me to further another.

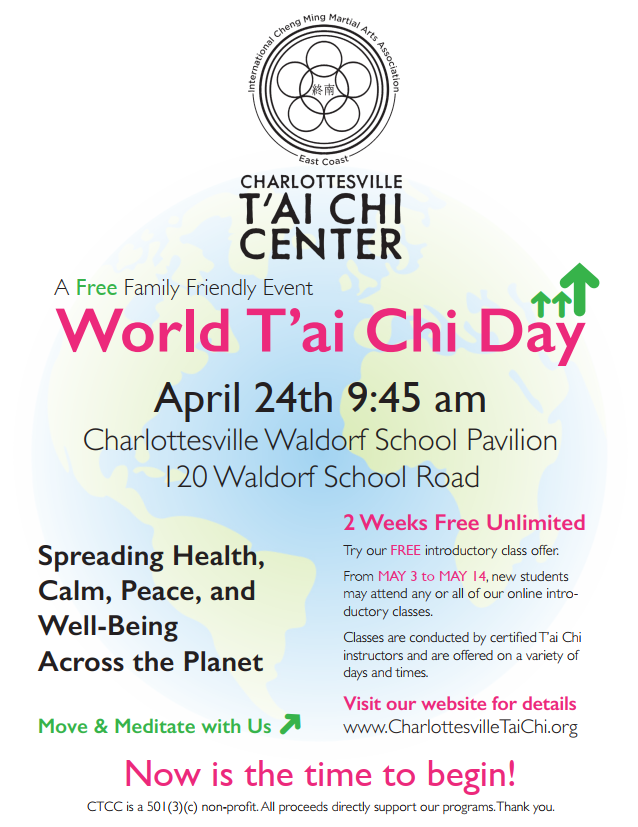

World T’ai Chi Day is an annual free event where participants around the globe practice T’ai Chi at 10 a.m. (local time) on the last Saturday of April.

World T’ai Chi Day is an annual free event where participants around the globe practice T’ai Chi at 10 a.m. (local time) on the last Saturday of April.